How Obsidian.md changed my way of learning

When I was in High school I used to take notes with Microsoft Word. Since I was never fond of handwritten notes, it seemed to me like the best way of summarizing the books and the lectures I had to study. That was my main study plan: listen to the lecture, go home, put some notes on Word, filling the details on the book, trying to elaborate concepts and express them in my own words, and then ditch the book completely and study entirely on those notes.

I remember memorizing all the shortcuts to change a text from normal text to Heading 1, Heading 2, Paragraph, Bold, Italic etc… My pinky was hurting for how many times I was hitting that CTRL button.

Little I knew that Markdown was even a thing. Using characters to tell the computer how to format text? That was never even an idea I thought of, until it came the second year of my Bachelor’s degree, when I was introduced to Notion.

Let me be clear, I saw some Markdown before that event, but it never stuck to me. During my first two years of my Bachelor’s I was using Google Docs, mainly because it was free, and it was cloud-based. Of course now the shortcuts for text formatting were all different, and I didn’t ever manage to learn those, mostly because my (international layout) keyboard had some hard times with those (Heading 1? Nah, put a diamond symbol in there, it’s way better).

Anyhow, when I switched to Notion everything changed. I discovered that it used a semi-Markdown syntax to format the text, and I also discovered that I could enter equations with a semi-latex syntax, and also pieces of code! It was amazing, the note-taking flow had never been this smooth, until I heard about Obsidian, around my second year of my Master’s degree.

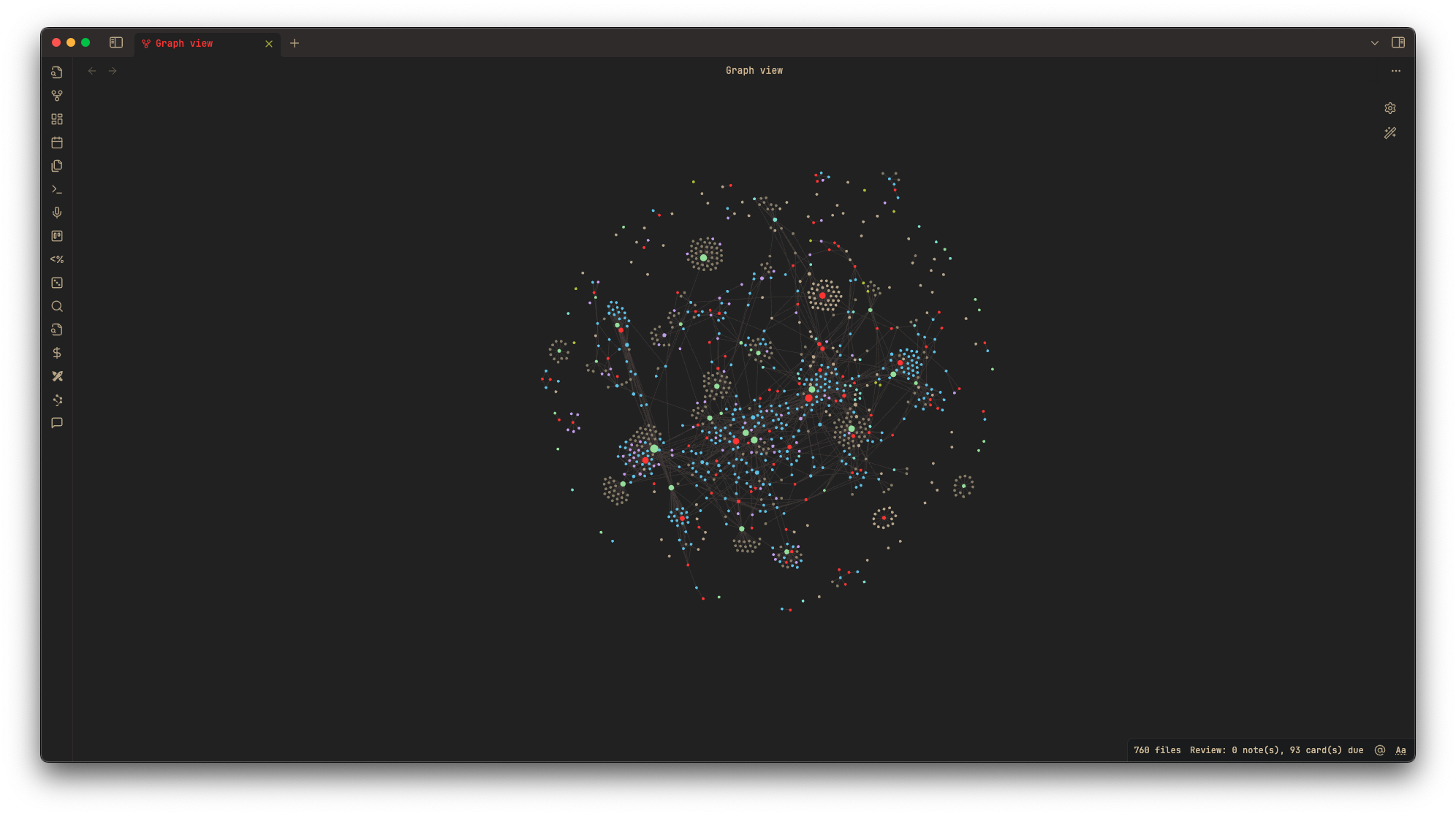

Most of the time Obsidian is advertised by content creators and other influential people online as a less bloated, faster and local alternative to Notion. In that period of time I was trying to be more interested in the privacy and ownership of my data, so the fact that the notes were just pure markdown files saved on my computer was the selling point that had me switching to Obsidian (and the amazing connection graph it produces from the notes of course, how couldn’t it be?).

Now, that’s just satisfying as hell to stare at.

Now, that’s just satisfying as hell to stare at.

During this time I was also learning vim motions, and was almost ready to switch from VSCode to Neovim, just to spice things up a little bit, be a little more minimal and (yet again) being more privacy-concerned with my data.

Wandering around on the internet, seeing how other people were setting up Obsidian, I stumbled upon the concept of Zettlekasten. Then came a book called How to Take Smart Notes, by Sönke Ahrens. That book, alongside with the amazing feeling of the blazingly fast note-taking on Obsidian due to the pure Markdown syntax, and the satisfaction of jumping around pieces of text using vim motions, changed the way I took notes (and the way I think about new information when I’m learning) probably forever.

Let me elaborate: Zettlekasten can be translated into “Slip box”, which is a technique introduced and mastered by a German sociologist called Niklas Luhmann. It consists into taking atomic notes, which usually include one concept, and then connect those atomic notes together via links. Overtime, this technique will create a nested web of concepts.

Furthermore, when writing a note we are focusing thinking where to put the note, in which folder, in which paragraph of an already existing document, or in a new document. We are just focusing on two important things: the concept itself, and how it connects to other pieces of information we already know and wrote about.

Once we put a lot of notes with a lot of connections in the slip-box, we don’t need to do brainstorming anymore. Searching for ideas that we read in our brain can be exhaustive, instead we can just look into the slip box, and new ideas and questions can rise automatically.

This simple technique completely blew my mind. Whenever I have a new concept to learn, I can just focus on writing it in my own words, and thinking about how it may connect to other topics allows me to visualize that simple concept in the broader topic I’m researching, and sometimes it also shows me how that concept can actually connect to others at first disconnected topics.

The Zettlekasten taught me that notes are not linear, the way thinking is not a linear process. The brain itself makes all types of connections: one concept can trigger the memory of other concepts, which are then connected to other more concepts and ideas, then why not adapting the note-taking process to how the brain actually stores information? This completely changed the way I think.

Now, using the pure Zettlekasten method used by Luhman may not be perfect for everyone, and because of that in the course of the months I modified it a little bit in order to better suit my personal needs.

Here’s how it works for me:

- I’m reading a paper, let’s say the notorious “Attention is All You Need” by Vaswani et al. I create a new “Literature Note”, which is simply a note connected to the original PDF where I try to summarize the things I learned from that particular paper. Here usually I don’t put any links to other notes, apart from other cited papers that are also in other literature notes.

- From the paper I learn the concepts of “Self-Attention”, “Transformers” and “Why transformers work better with long sequential data over RNNs”. Here is where I create a new “Fleeting Note” for each argument. A fleeting note is just a note about a (usually, but not always) single argument. It stays in the fleeting folder until it’s still a major draft, one it starts to make sense, I put it in the “Permanent Notes” folder. If the note is about self attention, I may connect it to “Tranformers”, “The attention mechanism”, “Self-attention vs Cross-Attention”, “Why transformers work better with long sequential data over RNNs”, etc…

The fact that I can put whatever thing I want to learn into a single fleeting note stimulates me to want to learn more, since it’s super easy for me to do it, and connections will appear in a very natural way.

Before this method, there was a lot of friction when wanting to write something down, since I had to understand where to put it before, and understand what the general topic was. Let’s say I was taking notes in the linear way, that’s what I would do:

- Create a “Transformers.docx” document, where I would put everything about transformers, including the self-attention mechanism and why do they work better on long sequential sequences than RNNs. Now, if I’m learning how other types of attention mechanism work, where do I have to put it? I should create a new “Attention mechanisms.docx” document, or should I put everything in transformers? In the first case, should I remove the part about “Self-attention” from the “Transformers” document, or should I just leave it and maybe write it more in depth in the “Attention mechanisms” document? And how can I connect the two documents together? Furthermore, if I want to write about Vision Transformers and how do they differ from CNNs, where should I put this idea? Inside the Transformers document? Inside the CNN document? I a new document? I think you understand the pattern here.

If you sort by topic, you are faced with the dilemma of either adding more and more notes to one topic, which makes them increasingly hard to find, or adding more and more topics and subtopics to it, which only shifts the mess to another level.

- Sönke Ahrens - How To Take Smart Notes

Anyhow, I like to change, so maybe one day I will discover some other amazing technique and/or platform, so who knows.

If you’re reading this, and you are still using Microsoft Word, Google Docs, Notion, or other linear note-taking tool (yes I know you can link notes also in Notion, but the experience is not as smooth), no hate. Everyone has their way of doing things, damn, someone might even find himself comfortable in taking notes in PowerPoint, and that’s just fine. I’m just curious and open to new strategies on how to solve problems, and people will keep inventing and discovering new of them. Learning is ever-changing, and that’s the beauty of it.